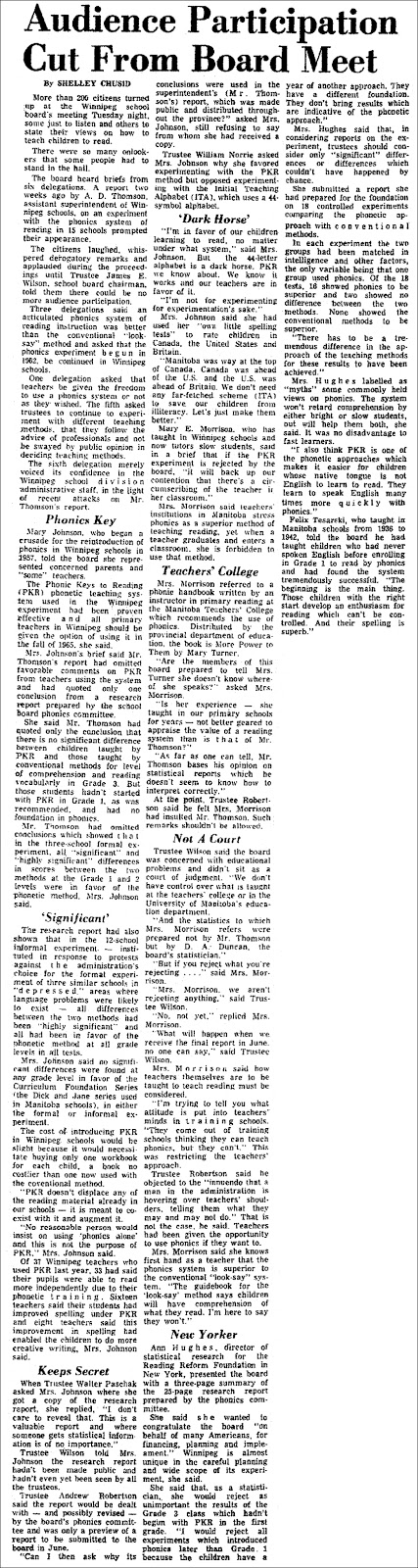

Mary Johnson had a student, 11 years old, who had learned to play the piano; presumably the girl had at least average intelligence. One day she showed up boasting that she had learned a new piece of music titled “Minuet.” Mary Johnson, stunned, pointed at the word at the top of the page and asked, “What does this say?” The big type read: Mimic.

“Joan had been able to read the piece of music after only six months’ piano lessons, and yet she could not read the simple title after four and a half years of public schooling! Her mother told me that Joan is ‘doing well’ in grade 5 at school and that she read several library books each week.”

So began the wonderful and heroic saga wherein Mrs. Mary Johnson discovered how bad things truly were, took on the Education Establishment, and probably saved millions of children from illiteracy. First, she made certain her own children could read; learned all the theories; and then she began to present analyses and proposals to the provincial authorities. The people in charge of Canadian education massively counterattacked.

Now she was up against the education professors; the publishing companies who made so many millions of dollars on Dick and Jane books; and that lobbying group called the International Reading Association (I.R.A.). You can imagine the sneer these phonies used in dismissing a housewife in 1957. And yet she just kept fighting. She should be a feminist icon.

The book records a 12-year battle to protect literacy in our schools. Of all the many excellent books about the Reading Wars, this might be the best. Only 170 pages long, it manages to be both intensely personal and high-scholarly. It shows you the kids, parents and schools struggling with look-say; the politicians ducking; the Education Establishment scheming for dollars and control.

|

| The brown strips are students' attempts to read "Mike hid a jar of gum drops in the shed." Page references below are from this book. |

If Mary Johnson’s attitude and determination sound familiar to us Fraser kids, it’s because Mom was one of Mary Johnson’s disciples. The same tenacity and resolve Mom applied to the campaign for lower speed limits on Portage Avenue were evident in the fight this other band of mothers employed to promote phonics.

Among Mom’s archives are years of letters, articles and news clippings related to what became known as the “Reading Wars.” The campaign files are comprehensive and numerous, and the long fight prompted Mary Johnson to publish Programmed Illiteracy in our Schools [2], printed by Hignell Printing Ltd. in 1970. (If I’m not mistaken, Hazel Fraser typed the manuscript.)

Like Mary, Mom was aghast at the school reading curriculum. The baby talk and dumbed-down Dick and Jane readers bored kids and underestimated their abilities to learn. These readers offered little vocabulary or stories of interest, a far cry from those used by our parents. Worse, students were expected to memorize words rather than sound them out, as though they were shapes. Mary discovered this with her own children. “Grant, at nine years of age, did not know what a vowel was and could not sound out the simplest word which he had not memorized at school. He would look at a three-letter word like mop and say blankly, ‘We haven’t taken it.’ ” [p. 1] When she approached Grant’s school for answers, Mary was told that he should just skip words he didn’t recognize, then go back and guess what they were.

|

| See Frasers bored. Bored, bored, bored. |

Mary found that this was a systematic problem, not limited to the few students she first came across. Clearly, school children were not being taught properly. Other concerned parents were also being brushed off with excuses, and the push for change soon found support among like-minded parents.

In 1955, American Rudolf Flesch published Why Johnny Can't Read. It became a best seller that attracted attention across North America. Flesch had studied everything published on phonics over the previous 40 years, and concluded, "In every single research study ever made phonics was shown to be superior to the word method; conversely, there is not a single research study that shows the word method superior to phonics." [3] The book remains a standard today and is recommended for teaching phonics to children.

In Manitoba, though, the "look-and-say" method, in which students just memorized whole words, was the only teaching method allowed. Teachers were restricted to the 1946 Basic Readers (the Dick and Jane series) published by W.J. Gage & Co., Toronto. No research had been conducted to gauge the curriculum's effectiveness, but for 20 years this Curriculum Foundation Series (CFS) was the sole authorized reading text that School Divisions could purchase. The accompanying Teachers' Guidebook advised that students "should not be asked to sound phonetic elements in isolation" and that "Children should not be asked to 'sound out' words. Phonetic analysis and blending should be done mentally, not vocally." [4]

|

| Mary Johnson |

Mary Johnson had discovered the dilemma quite by accident, but was not about to shrug it off. She examined the issue and was determined to find a solution. When politicians and educators refused to take her seriously, she set out to prove that sight reading alone was deficient. They could not dismiss her as a mere housewife, she reasoned, if she presented them with scientific results.

In the spring of 1957 the Manitoba government, under pressure from the Opposition, announced a five-member Royal Commission on Education, tasked with examining all points of view on educational problems below post-secondary education levels. The Commission was to review briefs from organizations and private citizens. Encouraged by the opportunity, Mary (and her husband Ernest) wrote to the Commission to have a submission included at their Fall hearing, and proceeded to conduct some serious research.

As Bruce Price [1] wrote:

The most vivid memory I have of Mary Johnson's cleverness is when she went to city parks and recruited kids to read for her. She tape-recorded their reading and then had the recordings played on local radio stations. And parents everywhere were stunned (and also relieved) to find that their child was not the only illiterate in town, that schools were creating massive numbers of kids who also stumbled, hesitated and guessed wildly.

Mary Johnson is famous for devising the simplest reading test of all. Children are asked to read these two sentences: "Mother will not like me to play games in my big red hat" and "Mike fed some nuts and figs to his tame rat."

Sight-word readers have no trouble with the first sentence; but they usually can't read the second sentence without mistakes because these words haven't been memorized; and the kids are unable to figure them out, despite the massive propaganda saying they can. Second-graders produce variations like this: "Made fed some nits and fudge to him take right."

|

| "I tape-recorded the oral reading of thirteen volunteers at this Winnipeg park in August, 1961." [p 46] Photo: Weekend Magazine |

As Mary herself wrote in her book, "The most outstanding characteristic of the children's reading was that it did not make sense, and they did not seem to expect it to do so. I found little evidence to support the claim of experts as the current system trained children to read for meaning. These children did not even pause to wonder at the nonsense they were reading aloud and they rarely went back and tried to correct themselves." [p. 11]

To her dismay, Mary was rebuffed by educators when she approached them with her ideas and results. She was dismissed as a meddling amateur trespassing on professional territory. One teacher told her that some children aren't ready for phonics, and just can't be taught. A speech expert at the Department of Education explained that children could not spell or read the word "bog" because it wasn't a suitable word in a province that didn't have bogs. An administrator excused children for reading "fringe" as "fingers" because they hadn't seen the word yet, but noticed letters sticking up and down, as in "fingers." He called this "intelligent reading." [p. 14]

The reading system teachers were allowed to use encouraged guesswork rather than sounding out letters and syllables. "New words were also guessed by comparing them with known words. The children were taught that game, for example, 'begins like go and looks like name and came except for the first letter." They were expected to figure out the right word from the sentence itself. "If a child asked for help in reading the word swim the teacher was supposed to say: 'It begins like swish and ends like him and it tells how we move in water.' " Mary despaired at how a student could ever read a word like Javex using this approach. [p. 21]

|

| Winnipeg Free Press, January 14, 1958 |

Mary took her reading tests to individual teachers, with approval from their principals. The results were predictable. Teachers had been cheated as much as the children, many felt, but the Winnipeg Superintendent of Elementary Schools was annoyed when he learned of the testing, and would not allow principals to release the results.

|

| A typical letter to the editor of the Winnipeg Free Press, from another fed-up parent. |

Armed with solid research, Mary and Ernest Johnson presented their case publicly to the Royal Commission on November 25, 1957. The comprehensive submission included 32 pages of tabulated spelling errors from 849 elementary students. Mary was pleased that the Commission "received us cordially, saying that our brief was just the type of presentation that they had hoped would be forthcoming from the public, and that they planned to conduct a thorough investigation." [p. 27]

| |

|

Neither would the Superintendent and Assistant Superintendent of Winnipeg Schools heed their own School Trustees, principals and teachers, who were very concerned about students' struggle and lack of progress. The administrators' attitude was that "one should simply not expect primary pupils to be able to figure out new words." [p. 31]

It became clear that the push for change would not be quick or easy. But the Johnsons were not about to give up, and were encouraged when they were invited to attend the first Canadian Conference on Education, to be held in February 1958 in Ottawa. It sounded like an ideal opportunity to present her findings, and Mary set out to conduct more research and prepare an extensive six-page brief. She mailed the brief to leading educators in Manitoba, and to the Royal Commission.

Again, however, Mary ran into resistance from the education establishment, and the brief that she had worked so hard to complete did not get a hearing at the Conference. She noted that, "The delegates, most of whom were professional educators, did not want copies of it and they did not want to discuss primary reading methods because they considered the subject 'too technical.' They spent two hours, instead, trying to arrive at a definition of the word education."

It seemed evident, Mary concluded, that: "When parents were silent about educational problems they were accused of apathy; when they presented proof of a problem and wanted to discuss it they were told it was too technical; when they persisted they were told that education was not their business." [p. 37]

Mary was not discouraged, however. Her cause was too important. She redoubled her efforts and continued her research.

The Winnipeg newspapers welcomed the controversy. It made good copy and prompted many articles and Letters to the Editors. As the Tribune editors told Mary, "You make the news, and we'll print it." After all, newspapers need readers!

|

| Gene Telpner's article in the September 10, 1958 Winnipeg Free Press illustrates Mary's unique approach to research. |

Parents were very concerned about their children's struggles when learning to read. Some left it to the educators, worried that their efforts to add phonics at home would only confuse children already being taught sight reading (memorization) at school. Mary reassured them that phonics training was still necessary:

Parents need to be very patient with the "educated guesser." He isn't being difficult or stupid -- he is just reading the way he has been taught -- by the shape of the word, by the first or last letters, by the "consonants which stick up." The retraining sessions are hard on all concerned and are seldom completely successful. The final product, like a retreaded tire or a made-over dress, may not be ideal but it is a big improvement." [p. 60]

|

| Hazel Fraser helped bring attention to Mary Johnson's campaign. Maclean's magazine covered the controversy from time to time. |

By the fall of 1959, the authorized Dick and Jane see-and-say approach was still entrenched. One change however, was reported by a few school districts. They had to add advanced classes for children who had learned to read at home and were way ahead of their peers!

When a second Canadian Conference on Education was advertised four years after the 1958 one, input and participation from parents was solicited. Mary found the appeal "exasperatingly hypocritical" and sent a letter to the Chairman that was quoted in newspapers across Canada. In it she called the appeal for input "a public relations gimmick" and told of the rejection her earlier brief had received. The second Canadian Conference was also the last; it was clear that so-called professional educators did not really want to hear from anyone else.

Mary's research went beyond the local schools and playgrounds. Her supporters wondered what the situation was like elsewhere, and whether that information could help make the case for phonics training in Manitoba. In 1958-59 the group wrote letters to the editors of 200 newspapers in eight English-speaking countries:

To the Editor:

When parents in Canada complain that their children cannot read print at first sight and can only recite from the school readers we are told, "The sight method of teaching reading, with incidental phonics, is used all over the world."

Many of us here are curious to know whether parents and teachers in your area are as dissatisfied with the results of this system as we are in Manitoba." [p. 63]The majority of the 300 replies confirmed that the sight reading method had created problems wherever it was used. Letters were received from 212 Americans, including a few ophthalmologists, consulted by parents whose children read badly. But the problem was the sight method, not eyesight. Seventeen American respondents blamed Communists for wanting to make the U.S. an illiterate nation.

Mary's team replied to each respondent in their survey, sharing her tests for students around the globe to complete. By the end of the 1959 school year, 1,664 Canadian, American, and English students had taken Mary's spelling test. Sixty-five sets of class results from 28 elementary schools were gathered. As might be predicted, the results from students who had been taught phonics were significantly better than sight readers.

The research abroad highlighted issues familiar to parents locally. "The one factor which seemed to be common to all of the trouble spots was the taboo, in teachers' colleges, against the straightforward teaching of phonics." In New Zealand, for instance, educators resistant to phonics quoted three American reading experts. But these experts were all authors of sight reading series, including Dick and Jane.

Mary and her supporters studied the results they received, and compiled a 14-page formal report that was mailed to the survey's respondents, to members of the Royal Commission, to Manitoba educators, and to editors and newsmen. The grassroots campaign gained support and momentum.

No longer did we in Manitoba feel isolated in our crusade for the teaching of real phonics. The evidence in favour of change was colourful, extensive and convincing, and we were optimistic that someday it would influence the teaching of reading all over the world -- including Manitoba. [p. 72]The reading controversy raged on between 1957 and 1959. During that time, the Manitoba Royal Commission on Education explored various ways of teaching reading, visiting classrooms, consulting teachers and administrators, and reading about the subject.

One author who promoted phonics and criticized the sight method was Dr. Charles C. Walcutt. He was invited to meet with the Royal Commission on May 7, 1959. Walcutt identified two factors that blocked change: (1) some professional educators simply resented outside criticism; and (2) publishers of sight method textbooks were behind elaborate and expensive campaigns to promote their series. Textbook companies made great profits producing books, teachers' guides, workbooks and promotional pamphlets, and sponsored experts (their authors) who misled educators and politicians about the merits of the sight method.

|

| Phonics supporters acknowledged that English was not an entirely phonetic language. Hazel Fraser promoted the idea of adapting new "common-sense spellings." |

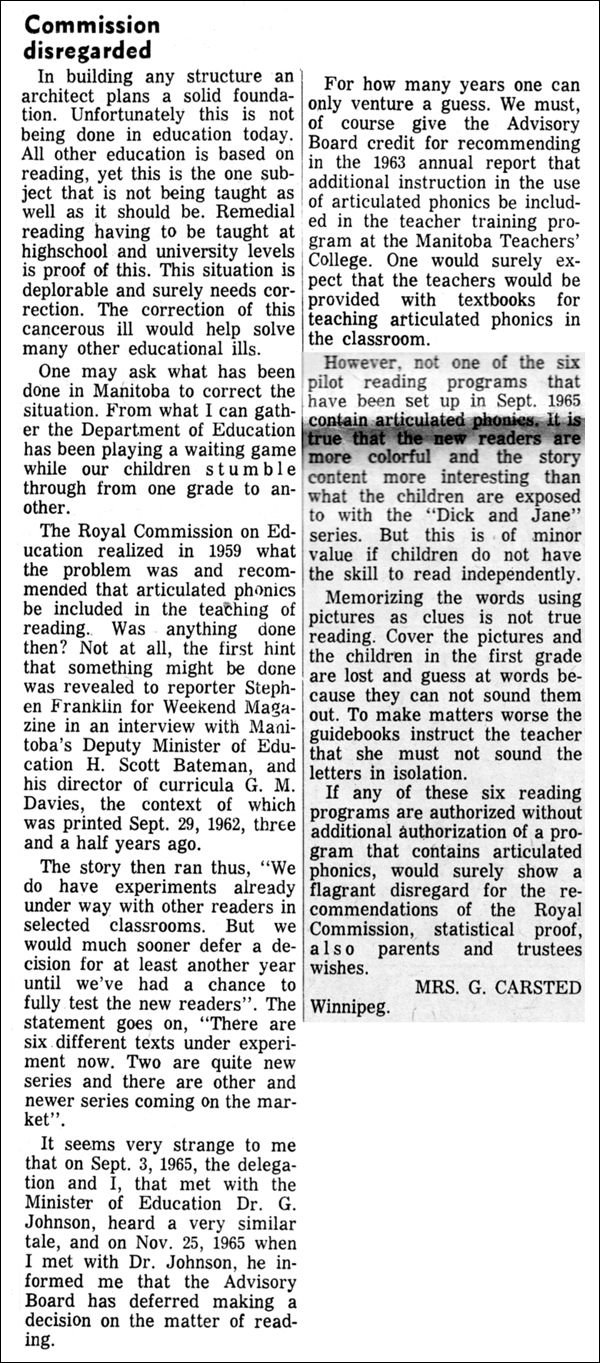

As an esteemed author and acknowledged educator himself, Dr. Walcutt was very influential and had indisputable credibility. He was able to convince the Royal Commission that a change was essential. In their final report released on December 1, 1959, the Commission recommended "the introduction of phonics (letters sounded in isolation) as an additional method of attacking new words very early in the initial stages of instruction." Parents were encouraged to teach their children phonics at home, and were reassured that children would not be confused if teachers used it as well. Further, the Commission's report stated that "the Commission believes that what is best in both methods will be put at the disposal of the child who is learning what is admittedly a very complex skill. ... The use of the phonetic attack as here recommended must be taught at the Teachers' Training College, and articles devoted to this topic should appear in the Manitoba School Journal for the benefit of teachers already in the field." [p. 75]

It was a welcome victory, but the Commission's role ended with the report. The question remained: Would the Manitoba Department of Education follow through?

Mary was right to be skeptical and wary. The Department of Education could take the recommendation under advisement and take all the time it wanted to consider it. Any changes would have to be approved by the Minister of Education, and then the Legislative Assembly. "The Minister of Education, in turn said that he was waiting to hear from his advisers in the Department -- and his advisers said they could not act until they were directed by the Minister. Everyone in the Department of Education, it seemed, was waiting patiently for someone else to act first." [p. 76]

The Department of Education stalled, supposedly "considering" the Commission's report. In the meantime, the Department continued to endorse the publishers of Dick and Jane. In one year, Gage and Company sponsored 19 reading seminars for primary teachers in Manitoba. These representatives pitched the status quo, dismissed Mary's research, and told teachers that there was already sufficient phonics in their teaching materials. English was not a phonetic language anyway, they explained.

The Commission's conclusion in 1959 to introduce phonics was utterly ignored, and the Legislative Assembly made no reference to it, even in year-end reports that focused on education. Mary expected the recommendations would be challenged, but ignoring the issue was even worse. Teachers were not even aware that phonics had been suggested by the Commission. "The report of the Royal Commission, far from stimulating action on the reading question, had led to a stalemate." [p. 80]

|

| Letter to the Editor, Winnipeg Free Press. "Experts" were often publishers' plants, even authors of the basal reading texts. |

Progress was also hampered by the International Reading Association (I.R.A.), a professional organization founded in 1956 with thousands of members. Mary joined the I.R.A. and discovered that each of its six presidents (1956-1961) was an author of sight reading series like Dick and Jane. The I.R.A. pitched the Dick and Jane series through publications and conferences, often financed by their textbook publishers. The Association dismissed Mary as a lone amateur, and claimed that their sight reading programs had more legitimate testing and research behind them.

Politically, the I.R.A. was powerful, representing as it did the organized voice of reading experts. However convinced a local politician might be of the need for a change in reading method, he could hardly expect to win an argument with a huge professional organization. And when the I.R.A. formally affiliated with the Manitoba Teachers' Society and was given representation on the Advisory Board to the Minister of Education, its influence in our province became all-pervasive. [p. 84]

|

| Mary sent Hazel Fraser a copy of her letter to Family Circle magazine, with her written comments. The two of them made a great team. |

|

| Letters to the Editors of the Winnipeg dailies kept the pressure on the Department of Education. |

The stalemate in Manitoba was depressing, but Mary was encouraged by supporters elsewhere. Mrs. Alice Vanarsdall, a Nebraska farm wife, toured the state in 1959 to ask teachers to run Mary's spelling tests. Alice reported that teachers who had learned to read under the sight method were themselves poor spellers, and some student teachers scored at the grade 5 level on reading tests. Rural parents reported that children spent hours on school buses and were too exhausted to receive supplementary reading lessons at home. They needed better instruction from the schools.

Similar deficiencies were reported from frustrated parents and teachers across North America. Hilda Mitchell, a former teacher in North Carolina, was particularly creative. She wrote a handbook titled Confusion, in which she used symbols rather than letters, to illustrate how learning words as wholes, by visual memorization, was so difficult. In Manitoba, former Premier Douglas Campbell, distributed Confusion to his colleagues, to help them understand the controversy over reading methods.

Voices demanding change grew louder, and grassroots groups started to organize.

It was the spontaneous and nationwide rebellion of parents and many teachers against the tyranny of sight method reading programs that culminated in the formation of the Reading Reform Foundation. This non-profit organization, with headquarters in New York City, was established in October 1961, with these declared goals: "education of parents, teachers, public authorities and the nation generally on the nature and extent of the reading crisis, its cause and its cure; coordination of the numerous local reform movements already active; creation of an informed public opinion in favour of eradicating the harmful whole-word memorization system. [p. 95]In Manitoba, the campaign for phonics carried on. "The chief distinction of our small, informal group of parents and teachers was its persistence and concentration of effort. Publicly and privately, over and over again, we worked to inform and convince elected members of the Winnipeg School Board and the Manitoba Legislature that reading beginners needed articulated phonics, and that teachers should be allowed to order phonics textbooks out of Government grants." [p. 97]

|

| The Department of Education would not make phonics materials available to the general public. |

|

| This reply was not unexpected. |

The media supported the group's efforts, printing letters to the editor, reports of Home and School debates, and explaining children's test results. Radio and TV stations played tapes of children struggling to read. Research results were sent by Mary and her friends to the Winnipeg School Board, legislators and civil leaders, school principals and educators, and anyone else who seemed interested.

|

| The letter-writing campaign started early and lasted for years. |

Mary Morrison, a retired junior high school teacher, wrote a series of 22 articles on education for the Winnipeg Tribune. She revealed to all that the Royal Commission's recommendations had been ignored. Media coverage stirred reaction from parents and others. University professors admitted they were frustrated by their students' poor command of English.

The strength and urgency of public opinion on the need for change was crystallized by a resolution passed at the 1961 School Trustees Convention: unanimous approval was given by 400 voting delegates to this resolution:

Whereas, At present the teaching of reading in the elementary grades leaves much to be desired, as is shown by the necessity for remedial procedures in some high schools, and by complaints from many parents that their children are unable to read satisfactorily on completion of the elementary grades; therefore,

Resolved, That the Department of Education be requested to give more emphasis to the phonics method of teaching reading in the elementary grades, and that adequate instruction be given in the Teachers College on how to teach by this method. [p. 99]

|

| The fight for phonics was not limited to Winnipeg, Manitoba. |

Andrew Moore, Ph.D., a Winnipeg School Trustee, supported the demand for phonics. As a retired principal and school inspector with several degrees, he had a lot of credibility. In a letter to the Tribune, he lamented that the Public Schools Act made phonics against the law, because it prohibited teachers from using any textbooks not authorized by the Minister of Education. Only one reading program was authorized, and it stated "Children should not be asked to sound out words. Phonetic analysis should be done mentally, not vocally."

This predicament, Moore wrote, was ridiculous. "No one system of teaching primary reading should be given such a monopoly. Teaching is (or should be) a profession, and this attempt to regiment all teaching of this most fundamental subject down one arbitrary groove is an insult to the teaching profession." [p. 100]

The Legislature was compelled to pay attention, and after much discussion it passed a resolution on May 1, 1962 asking the Advisory Board to the Minister of Education "to examine the program for the teaching of reading in elementary grades with a view to its improvement." [p. 101] After much deliberation, in the spring of 1963 the Board forwarded to the Minister of Education a recommendation that Manitoba teachers' colleges provide instruction in phonics.

|

| Hazel Fraser was interested in all subject areas, not just reading. |

Official approval for a change in teaching methods was an important victory in the six-year fight for phonics. The required next step was for the Minister of Education to authorize suitable textbooks.

|

| Letters to Editors kept the campaign in the public eye. |

In response to the Legislature and public demand for change, the Winnipeg School Division decided to compare the phonic and sight methods of teaching reading. The Economy Company, publishers of Phonetic Keys to Reading (PKR), provided extensive research. In their phonics approach, children were taught separate letter sounds and how to sound out words when they started grade 1. PKR workbooks were also provided.

|

| Hazel Fraser taught her kids phonics, and it showed. Her son and eldest daughter were reading Pierre Berton at ages 11 and 9, respectively. |

There was much debate over the experiment being planned. A committee of three Winnipeg school trustees, led by Dr. Andrew Moore, was formed to oversee the three-year research project. A plan was eventually established, and in September 1962 about 900 Winnipeg children began learning to read with the phonics approach.

Teachers using the PKR method noticed an improvement in their students' progress within a few months. Students could attack new words independently, their spelling and comprehension improved, and they were eager to read.

From 1962 to 1965 over one hundred teachers had the opportunity to use the PKR program. It was their personal experience and satisfaction with the method which helped to keep the experiment operating and expand the use of the program. [p. 108]The experiment garnered much interest beyond Manitoba. A similar study undertaken by Ann Hughes, an American educator and statistician, summarized results from 18 similar experiments in the U.S. comparing PKR with sight method programs. "Out of the eighteen experiments, sixteen showed phonics to be superior, and two showed no difference between the two methods. None showed the sight method to be superior." [p. 108]

|

| Phonics was top of mind even on family vacations. Mom received a grateful letter from her friend Margaret. |

|

| Hazel Fraser checked out the reading situation with the Ontario relatives during a family holiday in 1963. |

|

| The Hay Wingo was the preferred phonics textbook. Hazel Fraser bought several copies and shared them with other parents, and with St. Charles School. Typical pages are shown below. |

|

| Instead of sending her twins to the private kindergarten down the street, Mom used the mornings to give us phonics lessons and saw to it that we could read before we entered grade 1. |

|

| To ensure we weren't just memorizing (heaven forbid!) Mom would make us read the lines backwards. |

Research results locally were conclusive, and parents pressured the School Board for change. "From 1964 to 1966, seven separate delegations of parents pleaded for the continuation and/or expansion of PKR in classrooms where teachers wished to use the program." [p. 109]

In spite of the growing demand, and proof of the value of the phonics approach, resistance from the administration remained, and spread down through the school system. Principals and others were not willing to admit that the see-and-say method was the poorer choice. They clung to their authority and kept teachers in the dark. Results of the three-year experiment were buried, and its methodology was criticized.

|

| Winnipeg Free Press, September 4, 1965. |

The secrecy which surrounded the written reports prevented many people from forming an opinion based on all the facts. No effort was made by the administration to forward statistical reports on the experiment to the Advisory Board, nor even to supply the reports to other school districts on request. The report became so notoriously hard to get, in fact, that they were likened to Fanny Hill at one school board meeting and it was facetiously suggested that they be mailed out in plain brown covers. [p. 112]

|

| Winnipeg Free Press, March 3, 1965 |

|

| Winnipeg Tribune, August 1, 1964 |

|

| Winnipeg Free Press, March 10, 1965 |

The final report of June 1965 "showed that the classes which had been taught PKR from the beginning of Grade I outscored their controls by 17 to 0 in the administration's three-year experiment, and by 114 to 5 in the twelve-school experiment." Impressive, and yet the report's conclusion noted, "in the end the two methods of teaching reading will produce approximately the same results." [p. 115]

Dr. Moore challenged the report's inaccurate conclusion, which was clearly not supported by the facts. He submitted a 72-page report to the Winnipeg School Board and the Minister of Education that countered the inaccuracies and misinterpretations. It was clear that PKR pupils outscored those taught by Dick and Jane, and teachers favoured the phonics program. Students did, too; they were more independent in reading and showed an increased interest in it.

|

| Hazel Fraser kept an eye on media coverage and wanted editors to take note. |

The negative evaluation of PKR was not unanimous, though, and on August 24, 1965, Winnipeg trustees passed a motion permitting Winnipeg schools to use PKR at the discretion of the administration.

This discretion, however, was of little consequence, as the administration continued to throw up roadblocks:

- Orders of PKR books were not invited until school had already started that fall.

- Principals were canvassed by telephone for their PKR orders and told that the Department of Education would soon be authorizing a new phonic-type basal series, which would make PKR obsolete.

- Trustees were told that principals did not want to use PKR and had not ordered it.

- Written orders for PKR from principals were not filled.

- The trustees' motion re PKR was interpreted by the administration to mean that it was to be used for remedial instruction only.

- Remedial instruction with PKR was forbidden.

- PKR materials remaining in the schools were confiscated.

- Teachers were forbidden to follow the PKR method without appropriate materials. [p. 119]

While continuing to criticize detractors as amateurs spouting nonsense, the administration pretended to be open to ideas. In spite of growing demands from teachers and parents, and credible research results, their actions and dismissals continued to blanket any progress that had been made.

... the opinion of the administration had more influence over the teaching of reading in Manitoba than all of the objective research which had involved thousands of children and 144 teachers during a three-year period. By the fall of 1966 not one Grade I class in Winnipeg was using the PKR books. [p. 120]

|

| Winnipeg Tribune, September 4, 1965 |

|

| Letter to the Editor, Winnipeg Free Press, December 11, 1965 |

The 1962-65 experiment had proven PKR's value, and teachers had been convinced of the superiority of phonics-based methods. Private and parochial schools, which were less supervised and very progressive, were the first to endorse phonics. They switched from Dick and Jane to reading programs like the Beacon Readers, or Open Court series. Children were taught letter sounds and how to sound out words.

PKR materials were slowly finding a place in Winnipeg schools, and by 1964 PKR workbooks were being used in 86 public school classrooms. The Department of Education was prepared to provide some funding for the switch, and established a sub-committee tasked with examining alternatives to the Dick and Jane series.

|

| "It is up to local school boards to immediately investigate this supplement..." |

The sub-committee was given the Research Report on the PKR experiment nine months after it was published and only after Mr. Campbell confronted the Minister of Education about it. After the sub-committee recommended that PKR be used in conjunction with a new basal series, the Department of Education ignored the advice and added four sight method proponents to the committee.

|

| March, 1965. Mary Johnson expects action! |

It was no surprise when six basal sight method series were chosen for consideration. None taught separate letter sounds or how to sound out words. And none of the programs had statistical research behind them. Some hadn't even published guidebooks yet. This didn't concern the Department of Education, which claimed it was not interested in proper research-based evaluation of the programs because it was too much work.

|

| Letter to the Editor, Winnipeg Tribune, January 15, 1966 |

|

| Parents were getting impatient. Their children were struggling and not getting any younger! |

Many wondered why publishers didn't get on board with phonics and incorporate it in their materials. Why were they so adamant about protecting the sight method? The answer was often financial. Phonics, Mary explained, is simply cheaper to teach and is not as profitable for publishers:

Children who learn the separate letter sounds and how to sound out words from the beginning of Grade I become independent readers in six months. They are able to read whatever interests them at their level of comprehension and therefore do not provide a captive market for the controlled vocabulary readers and workbooks of any one publishing company. [p. 124]Quite simply, children taught phonics need fewer workbooks, and "It is the consumable workbooks which form the backbone of the basal series trade, and which represent at least 80 per cent of the annual cost of teaching reading under this system in the primary grades." [p. 125]

Phonics is a threat to a publisher's bottom line. Children's failure "creates the demand for follow-up, remedial textbooks, skill-teaching kits and 'educational hardware.' " As Mary lamented, "Unfortunately, for the children, there is more commercial profit in illiteracy than in independent reading." [p. 126]

|

| Letter to the Editor, Winnipeg Tribune, February 12, 1966 |

It was no surprise in 1966 when the Canadian Reading Development series was chosen as a replacement for Dick and Jane. The publisher's branch manager was president of the Winnipeg I.R.A. Council, and Copp Clark Company made large donations to public schools. No reading tests had been conducted to evaluate the new (Janet and John) series prior to choosing it.

|

| "It is indeed heartening to see a revolt by teachers..." |

When the Leader of the Liberal Party, Mr. Gildas Molgat, argued that public hearings should be held on the reading issue, his resolution was defeated. The Minister of Education replied that, "We'd be wise to leave these professional matters in the various sensitive areas to our experts to bring in recommendations." [p. 128] As it turned out, Janet and John readers were already in stock at the Provincial Textbook Bureau.

|

| Winnipeg Free Press, June 7, 1966. Mary Johnson has concerns about the new, untested reading series. |

The Department's authorization to introduce the Janet and John readers and workbooks in the fall of 1966 meant that PKR workbooks could not be used instead, even if a school district wanted them. To do so without authorization would be a punishable offence under the Public Schools Act.

Teachers were more restricted than ever, and could not order supplementary materials, even if they were prepared to pay for them. Not one phonics textbook or reference book was listed by the Department of Education in its catalogues.

It was hard to believe that the department had succeeded in sidestepping the results of research, the views of teachers, and the needs of the children. It was even harder to believe that, in spite of all the first-hand, local experience with the failure of the sight method and with the enormous educational benefits of articulated phonics, a new sight reading program – unsupported by research – could so easily have been imposed on the schools. But this indeed was what had happened, and Manitoba pupils and teachers and the public generally would have to suffer the consequences for many years to come. [p. 130]

|

| Winnipeg Tribune. Goodbye? More like good riddance! |

Predictably, the Janet and John series proved just as inadequate as Dick and Jane, and the publisher's claims that it was more sophisticated did not pan out. Instead, it was more cumbersome and only confused children. They were expected to read by a circuitous method. "For example, the children were expected to read the new word digging by 'developing' it from big" rather than sounding out its syllables. [p. 134]

Many Grade 1 classrooms were unable to cover the material by the end of the school year, and many teachers felt the series was even worse than Dick and Jane. Mary Johnson's testing with these new students added proof to the complaints.

In the Legislative Assembly, criticism and calls for change were again dismissed. The Department of Education blamed teachers for being resistant to change. Rather than admit they had made a poor, uninformed choice, the Department inexplicably authorized a second reading program in 1968, the Macmillan Mike and Mary series. It contained even less phonics than Janet and John, and had no research reports supporting it.

|

| Letter to the Editor, Winnipeg Free Press |

By 1968 open resistance to the new basal series had died down. All of the legitimate channels for protest had been exhausted and now, understandably, the news media has lost interest in the issue. Disillusioned and pessimistic, a few of us who had collaborated for many years banded together in July, 1968, to form the Reading Methods Research Association (R.M.R.A), adopting the following as our long-range goals:

Objectives: To encourage the practice of testing the effectiveness of initial reading instruction – Scientifically and thoroughly – prior to the publication and official adoption of school textbooks in which this instruction is incorporated; to improve the general standard of literacy among young people by encouraging the use of statistically proven methods of initial reading instruction.

Policies: To stimulate interest in the conduct of research on the effectiveness of various methods of the initial reading instruction; to establish an International Advisory Council of authorities on reading research and initial reading instruction; to supply information on methods and results of initial reading instruction. [pp. 136-137]R.M.R.A. membership included concerned parents, teachers, principals, administrators, and others, as well as American members of the American Reading Reform Association.

|

| Hazel Fraser brainstormed book titles on a grocery list. Programmed Illiteracy got the star. |

The fight continued, but when Mary Johnson completed her book in 1970, she remained determined and optimistic:

It has been a long journey from naïve housewife to leader of an educational organization. Along the way I have gained some insight into the problems of children, their teachers and parents – and I hope that the reader of this book has too.

The cause of the reading problem is simple enough: a vital ingredient, articulated phonics, is missing from the educational diet of primary school children. The solution is so simple that an untrained mother can provide it in the home: the missing ingredient must be added. When this is done even years later improvement in reading and spelling is dramatic and lasting.

It is the very simplicity of the solution, however, which causes it to be overlooked by commercial professional interests. Most of the inertia currently delaying the reform of reading instruction in primary classrooms can be traced to the fact that articulated phonics is inexpensive and uncomplicated: it lacks commercial value and professional status.

By contrast the human value of independence and reading and writing can hardly be measured: with this skill each one of us can learn that will from the past; be heard today; and leave a message for the future.

It has not been easy to promote an educational skill for its human value alone, nor to do it from outside the teaching profession. But for some of us there has been no choice; it would have been so much harder to do nothing.

|

| The negative effects of sight reading methods lasted a long time. Letter to the Editor, Winnipeg Tribune, November 19, 1971 |

Mary Johnson fought for phonics for years and years, well beyond 1970, when her book was published. You might think she'd be happy to close the book on the issue, but it occurred to her that a proper reading method would also benefit new immigrants struggling to learn English. She turned her attention to English as a Second Language (ESL) methods and the needs of new citizens. In February 1972 the Reading Methods Research Association was disbanded.

In 1991 Mary Johnson was inducted into Winnipeg's Citizens Hall of Fame. The honour includes a bust of Mary in Assiniboine Park sculpted by renowned artist Leo Mol. The Hall of Fame was established to recognize "citizens who have contributed to Winnipeg's quality of life with exceptional achievements in leadership and community service. The inductee's achievements may be local, national or international in scope."

|

| Mary Johnson, sculpted by Leo Mol. |

The write-up accompanying the honour reads as follows:

LITERACY ADVOCATE

Mary Johnson began her crusade against illiteracy in the 1960s. She was vocal in her advocacy of the phonetic method of teaching children to read, so when her methods ran into opposition, she began to publish her own books on the subject. She formed the reading-related publishing company, Clarity Publications. That her methods work is shown by the widespread support her work eventually received.

While her initial work was with school children, she came to realize that her methods could be used to teach English as a second language to newly-arrived Canadians. In this direction, Johnson not only inspired a knowledge of English, but instilled a compassion in the new arrivals of their adopted country.

Johnson was a fixture at the International Centre, where she greeted each new arrival with the goal of making them feel they were a welcome addition to the community.

For her part, Johnson also recognized the importance of the International Centre and left as a donation the copyright to her 14 workbooks.

Her Foundations for Literacy workbook goes far beyond being solely an aid, as she understood the intricacies of spelling and simplified it to become readily comprehensible to the average person.

There is no question that Mary Johnson earned the recognition and accolades she eventually received. She was the general this war needed.

OBITUARY:

|

| Obituary, Winnipeg Free Press, June 18, 1990 I was sorry to see this posted on the bulletin board in my building. Had I known she lived here, I would have introduced myself. |

[1] Bruce Deitrick Price, "Hurray for Mary Johnson -- A Great Educator (and a Canadian)," in Canada Free Press, February 3, 2011

http://canadafreepress.com/articles-travel/32873

[2] Mary Johnson, Programmed Illiteracy in Our Schools (Clarity Books, 1970)

[3] Bruce Deitrick Price, "The Most Obvious Conspiracy in the History of the World," in American Thinker, March 21, 2014

http://www.american thinker.com/articles/2014/03/most_obvious_conspiracy.html

[4] Mary Johnson, "Time for Change," in Spelling Progress Bulletin, Spring 1966

http://spellingsociety.org/uploaded_bulletins/spb66-1-bulletin.pdf

LINKS

- Brief to the Canadian Conference on Education, February 1958, by Mary and Ernest Johnson

- How to create functional illiteracy in 7 easy steps, by Bruce Deitrick Price

- Letters to the Editor (Winnipeg Free Press and Winnipeg Tribune)

⇧ BACK TO TOP

No comments:

Post a Comment